Abstract

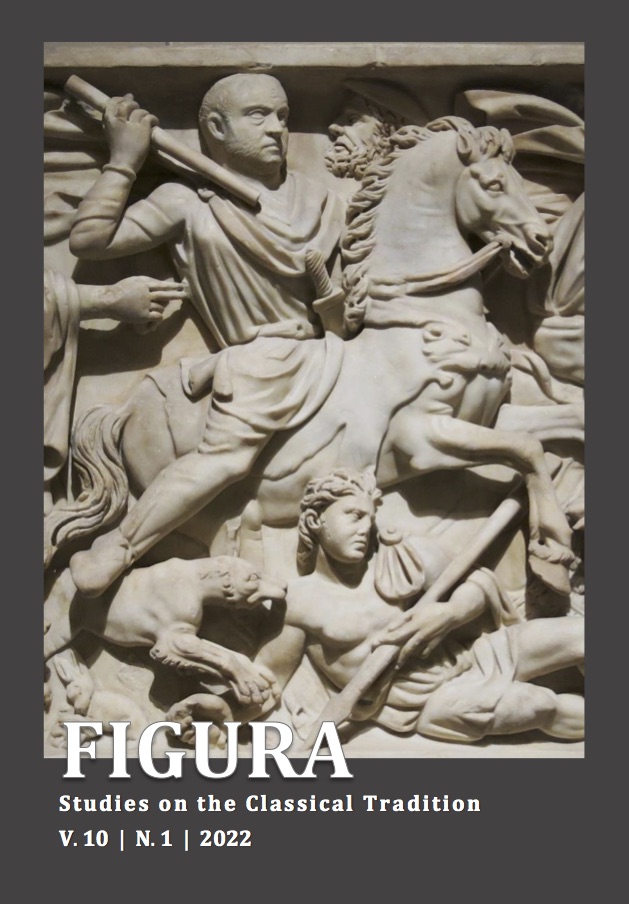

This article surveys the takeover of Roman Hunt Sarcophagi by Christians in Late Antiquity, with a special focus on the monument for Bera in San Sebastiano ad Catacumbas . It is typically argued that their selection of these monuments was motivated by the same “worldly” concerns as their pagan neighbours. This assumption will be challenged here by exploring the potential for resemanticization in a new Christian context, and – in the case of Bera in particular – the complex intersections of gender, virtue and religion in this period.

References

ANDREAE, B. Motivgeschichtliche Untersuchungen zu den römischen Schlachtsarkophagen. Berlin: Gebr. Mann 1956.

ANDREAE, B. “Bossierte Porträts auf römischen Sarkophagen. Ein ungelöstes Problem”. In: ANDREAE, B. (Ed.). Symposium über die Antiken Sarkophage. Pisa 5.12. September 1982, Marburger WinckelmannProgramm 1984. Marburg/Lahn: Verlag des Kunstgeschichtlichen Seminars, 1984. p. 109128.

ANDREAE, B. Die Sarkophage mit Darstellungen aus dem Menschenleben II. Die römischen Jagdsarkophage. Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1980.

AUGUSTINE. City of God, Volume II. Books 47. Green, W.M. (Transl.). Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1963.

BALMACEDA, C. Virtus Romana. Politics and Morality in the Roman Historians. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2017.

BEJAOUI, F. “Le sarcophage de Lemta” In: Koch, G. (Ed.). Akten des Symposiums "Frühchristliche Sarkophage". Marburg, 30.6.4.7.1999. Mainz: von Zabern, 2002, p. 1318.

BERGMANN, M. Studien zum römischen Porträt des 3. Jahrhunderts n. Chr.. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt Verlag, 1977.

BIELFELDT, R. “Vivi fecerunt. Roman Sarcophagi for and by the Living”. In: HALLETT, C.H. (Ed.). Flesheaters. An International Symposium on Roman Sarcophagi. Berkeley 1819 September 2009. Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag, 2019, p. 6596.

BIRK, S. “Women or Man? CrossGendering and Individuality on Third Century Roman Sarcophagi”. In: ELSNER, J.; HUSKINSON, J. (Eds.). Life, Death and Representation. Some New Work on Roman Sarcophagi. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2011. p. 229260.

BIRK, S. Depicting the Dead. SelfRepresentation and Commemoration on Roman Sarcophagi with Portraits. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2013.

BIRK, S. “Using Images for SelfRepresentation on Roman Sarcophagi”. In: BIRK, S.; KRISTENSEN, T. M.; POULSEN, B. (Eds.). In: Using Images in Late Antiquity. Oxford/Havertown: Oxbow Books, 2014, p. 3447.

BIRK, S. “The Christian Muse. Continuity and Change in the Representations of Women on Late Roman Sarcophagi”. In: KOCH, G. (Ed.). Akten des Symposiums Römische Sarkophage. Marburg, 2.8. Juli 2006. Marburg: Eigenverlag des Archäologischen Seminars der PhilippsUniversität, 2016, p. 6372.

BORG, B.E Crisis and Ambition. Tombs and Burial Customs in ThirdCentury CE Rome. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

BRANDENBURG, H. Roms frühchristliche Basiliken des 4. Jahrhunderts. Munich: Heyne, 1979.

BRANDENBURG, H. “Ende der antiken Sarkophagkunst in Rom. Pagane und christliche Sarkophage im 4. Jahrhundert”. In: KOCH, G. (Ed.). Akten des Symposiums "Frühchristliche Sarkophage". Marburg, 30.6.4.7.1999. Mainz. P. von Zabern, 2002.

BRATTON, S.P. Environmental Values in Christian Art. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2007.

BRAVI, A. “The Art of Late Antiquity. A Contextual Approach”. In: BORG, B.E (Ed.). A Companion to Roman Art. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2015, p. 130149.

CAIN, A. Jerome's Epitaph on Paula. A Commentary on the Epitaphium Sanctae Paulae. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013.

CARDAUNS, B. M. Terentius Varro. Antiquitates rerum divinarum I. Die Fragmente. Mainz/Wiesbaden: Steiner, 1976.

COBB, L.S. Dying to Be Men. Gender and Language in Early Christian Martyr Texts. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008.

D’AMBRA, E. “Daughters as Diana. Mythological Models in Roman Portraiture”. In: Bell, S.; Hansen, I.L. (Eds.). Role Models in the Roman World. Identity and Assimilation. Ann Arbor: The University of Michigan Press, 2008, p. 171183.

DEICHMANN, F.W. et al. Repertorium der ChristlichAntiken Sarkophage 1. Rom und Ostia. Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1967.

DOERFLER, M.E. “Coming Apart at the Seams. CrossDressing, Masculinity, and the Social Body in Late Antiquity”. In: UPSONSAIA, Kristi, DANIELHUGHES, C.; BATTEN, A.J. (Eds.). Dressing Judeans and Christians in Antiquity. Farnham: Ashgate, 2014, p. 3751.

EISENHUT, W. Virtus romana. Ihre Stellung im römischen Wertsystem. Munich: Wilhelm Fink, 1973.

EISENHUT, W. “Virtus als göttliche Gestalt”. In: Paulys Realencyclopädie der classischen Altertumswissenschaft. Neue Bearbeitung. Suppl. XIV. Stuttgart: J. B. Metzlerscher, 1974, p. 896910.

EWALD, B.C. Der Philosoph als Leitbild. Ikonographische Untersuchungen an römischen Sarkophagreliefs. Mainz: von Zabern, 1999.

FENDT, A. “Schön und stark wie eine Amazone. Zur Konstruktion eines antiken Identifikationsmodells. Amazonendarstellungen auf einem AchillPenthesileaSarkophag als Bilder für Vorstellung von Weiblichkeit im 3. Jh. n. Chr.”. In: Socj, N. (Ed.). Neue Fragen, neue Antworten. Antike Kunst als Thema der Gender Studies. Berlin: Lit, 2005, p. 7794.

FIOCCHI NICOLAI, V. et al. Roms Christliche Katakomben. Geschichte – Bilderwelt – Inschriften. (2nd Edition). Regensburg: Schnell & Steiner, 2000.

GANSCHOW, T. “Virtus”. In: Lexicon iconographicum mythologiae classicae VIII. Zurich/Munich: Artemis Verlag, 1997, p. 273281.

GOLD, B.K. “Remarking Perpetua. A Female Martyr Reconstructed”. In: MASTERSON, M.; RABINOWITZ, N.S.; ROBSON, J. (Eds.). Sex in Antiquity. Exploring Gender and Sexuality in the Ancient World. London/New York: Routledge, 2014, p. 482499.

GOLDBERG, E.J. In the Manner of the Franks. Hunting, Kingship, and Masculinity in Early Medieval Europe. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2020.

GRASSINGER, D. Die mythologischen Sarkophage I. Achill, Adonis, Aeneas, Aktaion, Alkestis, Amazonen. (Die antiken Sarkophagreliefs 12, 1). Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1999.

HANSEN, I.L. “Gendered Identities and the Conformity of MaleFemale Virtues on Roman Mythological Sarcophagi”. In: Lovén, L.L.; Strömberg, A. (Eds.). Public Roles and Personal Status. Men and Women in Antiquity. Proceedings of the Third Nordic Symposium on Gender and Women’s History in Antiquity Copenhagen 35 October 2003. Sävedalen: Paul Åströms, 2007, p. 107121.

HEFFERNAN, T.J. Sacred Biography. Saints and Their Biographers In the Middle Ages. New York: Oxford University Press, 1988.

HEMELRIJK, E. Matrona Docta. Educated Women in the Roman Elite from Cornelia to Julia Domna. London/New York: Routledge, 1999.

HIMMELMANN, N. Typologische Untersuchungen an römischen Sarkophagreliefs des 3. Und 4. Jahrhunderts n. Chr. Mainz: von Zabern, 1973.

HOTCHKISS, V.R. Clothes Make the Man. Female CrossDressing in Medieval Europe. New York: Garland, 1996.

HUSKINSON, J. Roman Children’s Sarcophagi. Their Decoration and its Social Significance. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996.

HUSKINSON, J. “‘Unfinished Portrait Heads’ on Later Roman Sarcophagi. Some New Perspectives”. Papers of the British School at Rome, London/Cambridge, v. 66, p. 129158, 1998.

HUSKINSON, J. “Women and Learning. Gender and Identity in Scenes of Intellectual Life on Late Roman Sarcophagi”. In: MILES, R. (Ed.). Constructing Identities in Late Antiquity. London/New York: Routledge, 1999, p. 190213.

HUSKINSON, J. “Representing Women on Roman Sarcophagi.” In: MCCLANAN, A.L.; ENCAMACIÓN, K.R. (Eds.). The Material Culture of Sex, Procreation, and Marriage in Premodern Europe. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002, p. 1131.

KJÆRGAARD, J. “From Memoria Apostulorum to Basilica Apostulorum. On the Early Christian cultcentre on the Via Appia”. Analecta Romana Instituti Danici, Copenhagen, 13, p. 5976, 1984.

KOCH, G. Die mythologischen Sarkophage VI. Meleager. (Die antiken Sarkophagreliefs 12, 6.). Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1975.

KOCH, G. Frühchristliche Sarkophage. Munich: C. H. Beck, 2000.

KUEFLER, M. The Manly Eunuch. Masculinity, Gender Ambiguity, and Christian Ideology in Late Antiquity. Chicago/London: University of Chicago Press, 2001.

KUNST, C. “Wenn Frauen Bärte haben. Geschlechtertransgressionen in Rom”. In: HARTMANN, E.; HARTMANN, U.; PIETZNER, K. (Eds.). Geschlechterdefinitionen und Geschlechtergrenzen in der Antike. Stuttgart: F. Steiner, 2007, p. 247161.

LEWIS, C.T.; SHORT, C. A Latin Dictionary. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1879.

LEWIS, S. “The Iconography of Coptic Horseman in Byzantine Egypt”. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt, Princeton, 10, p. 2763, 1973.

MCDONNELL, M.A. Roman Manliness. Virtus and the Roman Republic. Cambridge/New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006

MIKOCKI. Collection de la Princesse Radziwiłł. Les monuments antiques et antiquisants d’Arcadie et du Château de Nieborów. Wroclaw: Wydawnictwo Polskiej Akademii Nauk, 1995.

MILHOUS, M.S. Honos and Virtus in Roman Art. PhD Thesis. Boston University, Prof. KLEINER, F.S.. Boston 1992.

PRUSAC, M. From Face to Face. Recarving of Roman Portraits and the LateAntique Portrait Arts. Leiden/Boston: Brill, 2011.

REINSBERG, C. Die Sarkophage mit Darstellungen aus dem Menschenleben III. Vita romana. (Die antiken Sarkophagreliefs 1, 3). Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 2006.

REIS, D.M. “Spec(tac)ular Sights. Mirroring in/of Acts”. In: DUPERTIUS, Rubén R., PENNER, T. (Eds.). Engaging Early Christian History. Reading Acts in the Second Century. Durham/Bristol: Acumen, 2013, p. 59100.

ROBERT, C. Einzelmythen II. HippolytosMeleagros. (Die antiken Sarkophagreliefs 3, 2). Berlin: Gebr. Mann, 1904.

RUSSELL, B. “The Roman Sarcophagus ‘Industry’. A Reconsideration”. In: ELSNER, J.; HUSKINSON, J. (Eds.). Life, Death and Representation. Some New Work on Roman Sarcophagi. Berlin/New York: De Gruyter, 2011, p. 119147.

SANDE, S. “The Female Hunter and other Examples of Change of Sex and Gender on Roman Sarcophagus Reliefs”. Acta ad Archaeologiam et Artium Historiam Pertinentia, Rome, v. 22, p. 5586, 2009.

SICHTERMANN, H. “Der GanymedSarkophag von San Sebastiano”. Archäologischer Anzeiger, Berlin, p. 462470, 1977.

SMITH, K.A. “Spiritual Warriors in Citadels of Faith. Martial Rhetoric and Monastic Masculinity in the Long Twelfth Century”. In: THIBODEAUX, J.D. (Ed.). Negotiating Clerical Identities Priests, Monks and Masculinity in the Middle Ages. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010, p. 86112.

STUDERKARLEN, M. Verstorbenendarstellungen auf frühchristlichen Sarkophagen. Turnhout: Brepols, 2012.

TOMMASI, C.O. “Crossdressing as Discourse and Symbol in Late Antique Religion and Literature”. In: CAMPANILE, D.; CARLÀUHINK, F.; FACELLA, M. (Eds.). TransAntiquity. CrossDressing and Transgender Dynamics in the Ancient World. London/New York, Routledge, 2017, p. 120133.

TUCK, S.L. “The Origins of Roman Imperial Hunting Imagery. Domitian and the Redefinition of virtus under the Principate”. Greece & Rome, Oxford, v. 52, p. 221245, 2005.

ULBERT, T.; DRESKENWEILAND, J. Repertorium der christlichantiken Sarkophage 2. Italien mit einem Nachtrag Rom und Ostia, Dalmatien, Museen der Welt. Mainz: von Zabern, 1998.

UPSONSAIA. Early Christian Dress. Gender, Virtue, and Authority. New York/London: Routledge, 2011.

VACCARO MELUCCO, A. “Sarcofagi romani di caccia al leone”. Studi miscellanei, Rome, v. 11, 19631964.

VAN HOUDT, T. et al.. “Introduction. The Semantics and Pragmatics of Virtus”. In: PAETOENS, G.; ROSKAM, G.; VAN HOUDT, T. (Eds.). Virtus Imago. Studies on the Conceptualisation and Transformation of an Ancient Ideal. Leuven/Dudley: Peeters, 2004, p. 126.

VIDÉN, G. “The Twofold View of Women. Gender Construction in Early Christianity”. In: Lóven, L.L.; Strömberg, A. (Eds.). Aspects of Women in Antiquity. Proceedings of the First Nordic Symposium on Women’s Lives in Antiquity, Göteborg 12 15 June 1997. Jonsered: P. Åströms Förlag, 1998, p. 142153.

VORAGINE, J.A.; GRAESSE, T. Legenda aurea. Vulgo historia lombardica dicta. Osnabrück: Zeller, 1965.

WARDPERKINS, J.B. “Nicomedia and the Marble Trade”. Papers of the British School at Rome, London/Cambridge, v. 48, p. 2369, 1980.

WILPERT, J. Erlebnisse und Ergebnisse im Dienste der christlichen Archäologie. Rückblick auf eine fünfundvierzigjährige wissenschaftliche Tätigkeit in Rom. Freiburg im Breisgau: Herder, 1930.

WOLF. Die Nekropole In Vaticano ad circum. Rome: 1977.

ZANKER, P.; EWALD, B.C. Mit Mythen leben. Die Bilderwelt der römischen Sarkophage. Munich: Hirmer, 2004.

ZIMMERMANN, N. “Catacombs and the Beginnings of Christian Tomb Decoration”. In: BORG, B.E (Ed.). A Companion to Roman Art. Hoboken: John Wiley and Sons, 2015, p. 452470.

ZIMMERMANN, N. “Catacomb Painting and the Rise of Christian Iconography in Funerary Art”. In: Jensen, R.M.; Ellison, M.D. (Eds.). The Routledge Handbook of Early Christian Art. London: Routledge, 2018, p. 2138.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Copyright (c) 2022 Sarah Hollaender